Lose the Plot

Despite ANORA's sweep, politics and beauty can't coexist at the Academy Awards.

Sean Baker’s Anora won basically everything at last night’s Academy Awards. This was surprising, though not because of the quality of the film (excellent) or its provocative subject—it’s a rags-to-riches story about a stripper from Brighton Beach who marries the son of Russian oligarchs—but because Baker seems to have successfully defended the project against unfounded claims of exploitation. In his acceptance speech, he (once again) thanked the sex worker community: “They have shared their stories, they have shared their life experiences with me over the years. My deepest respect. Thank you, I share this with you,” Baker said.

But it would be näive to mistake this recognition for some sort of political statement by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Consider one of the other award categories: best live-action short. As the usual platform for passively acknowledging various social and environmental causes, it’s been an easy target for certain critics, only for the wrong reasons. Describing this year’s picks, Jeanette Catsoulis writes in The New York Times that “there’s cruelty, injustice, and existential angst aplenty.” Among the unusually international group, including the Dutch writer/director Victoria Warmerdam’s winner, I’m Not A Robot, Catsoulis thinks that brutality is “a thematic through line that suggests any filmmaker seeking a statuette had better wake up and smell the oppression.”

Catsoulis may be right that these nominations are a “sign of the times,” but her own hostility to films motivated by politics says far more about American culture today than an awards show does. Even fans of the short films sell them short. In Variety, Peter Debruge describes I’m Not A Robot as the “only nominee chosen solely on the strength of its filmmaking (as opposed to the worthiness of its activist cause).” Maybe Debruge has a mole on the committee; maybe the film’s feminist message just didn’t grab him. In either case, when Catsoulis offers the backhanded praise that “luckily, a nasty scent doesn’t have to mean ugly visuals,” she is giving voice to a desire, broadly held among critics, to draw a neat distinction between politics and art of all kinds—a crass distinction that is both lazy as a review’s framing device and false as a way of describing these films in particular.

I’m Not A Robot did not win because it’s the most effective of the group, which it isn’t. I like the film, but the cowardice of its selection on both political and artistic grounds will be obvious to anyone who watches the rest. Given the unembarrassed polemical aims of feature films like Anora, The Brutalist, Conclave, and Sing Sing, it’s odd that only the short films are dismissed as they are. Formal efficiency does not have to provoke such willful ignorance. With limited time, themes will often be obvious, characters archetypal, the soundtrack on-the-nose. All right. But just as the mere mention of atrocity won’t discourage lovers of beauty, humane adults won’t be cowed by the award for best cinematography (or best actor with an AI-generated Hungarian accent).

I’m Not a Robot (2023)

At work one day, Lara, a music producer, flunks CAPTCHA after CAPTCHA. When she calls technical support, she learns it’s not a bug in the software: Lara’s boyfriend Daniel “collected” her from a company that reactivates the dead. Think: Christ picking up a refurbished Lazarus from the genius bar. The daily realities of sexism may be easier to ignore than the guns being waved around in the other films, but that doesn’t mean I’m Not A Robot is apolitical, as Debruge suggests. In this speculative thriller, Warmerdam has inverted the Turing test for the sex robot era. Suppose a machine can imitate a human so well that it adamantly denies it is a machine at all. Could it lead a meaningful life? Judging by the final scene, which starts on the roof and ends on the sidewalk, Lara isn’t convinced.

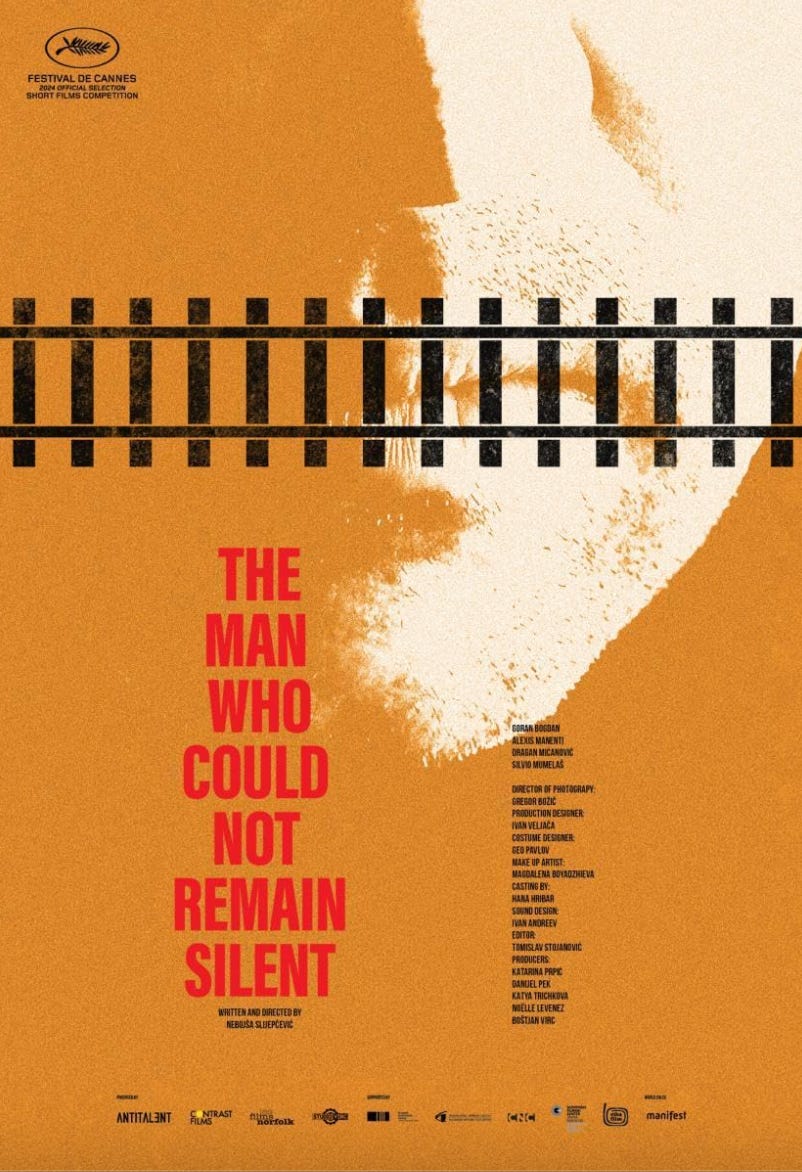

The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent (2024)

In this understated film from director Nebojša Slijepčević, we see a packed train car through the eyes of a world-weary chain smoker. Somewhere between Belgrade and Ban, the train makes an unplanned stop. From the window, the smoker sees armed men forcing their way aboard. He returns to his cabin and tells the five other passengers what he’s just heard: the soldiers are checking identification cards, probably looking for draft dodgers and arms dealers. Problem: The young man sitting across from him has none. Is he on the run? What about the two well-dressed older men? Or the young girls reading and listening to music? Just as we begin to work things out, there’s a knock at the door. In just 14 minutes, Slijepčević masterfully diverts our hair-trigger suspicions to ordinary people while unraveling the horror of the 1993 Štrpci massacre, one of several mass murders of Muslims committed by paramilitary groups in Bosnia and Herzogovina.

Anuja (2024)

Twelve-year-old Sajda Pathan was not cast as the lead in Anuja by chance. A former child laborer now in the care of an Indian nonprofit, Pathan plays a homeless girl asked to be in two places at once at eight a.m. on Tuesday. Option number one: Report for duty at the textile sweatshop where she works with her sister to help the sleazy manager do basic accounting. Option number two: Sit for a boarding school entry exam in the gentle Mr. Mishra’s sunny classroom. If she fails to show up for work, she and her sister—who live on their own—will both lose their jobs. And if she doesn’t take the test now, she may never get the chance again. Graves leaves the viewer to interpret which choice she will make, a degree of ambiguity that frustrated and impressed me.

A Lien (2023)

Don’t let the distracting wordplay in the title fool you: This movie makes the White House’s vile “ASMR: Illegal Alien Deportation Flight” look like an episode of Paw Patrol. Brothers and co-creators David and Sam Cutler-Kreutz have turned the underreported practice of ICE agents detaining immigrants at their scheduled green card interviews into one New York City family’s horror story. From the first scene in the car with frantic Sophia behind the wheel, Oscar trying to figure out which shirt is less wrinkled, and little Nina in the back blowing on duck whistle, the value of every second is harrowingly clear. Fifteen minutes is a long time to have your jaw clenched.

The Last Ranger (2024)

On his list of all 50 Oscar nominees, Vulture’s Joe Reid ranked Cindy Lee’s The Last Ranger second-worst of the live-action shorts (narrowly beating last night’s winner). “Certain live-action shorts (the ones that get nominated for the Oscar, at least) feel like a feature-length movie boiled down to The Moment That Changes Everything. Because of the time constraints, you see the moment coming a mile away and it all starts to feel a bit airless,” Reid writes. Sure, one might expect, when watching a film set on a South African game reserve, that someone will take a shot at an endangered rhinoceros. But Lee is more interested in who pulls the trigger and why—the negotiations of conscience that can’t be experienced in advance.

Thanks for reading. If you like reading about books and politics and want to help keep this newsletter free for everyone, consider subscribing for $5/month.

I have to wonder if Anora was also the anti-establishment vote, which seems the order of the day, and right on, in the right context, but not this one. Absurd, I thought. Then again, these award rituals are absurd. Cheers.